Three principles that will shape our future landscapes

Human creativity is marked across the whole surface of Earth. For thousands of years we have applied our imagination and inventiveness to shape, reshape, cultivate and harvest our native landscapes whilst contributing to the massive, and often destructive, changes to global environments that have transformed the planet. Today, we are faced with the very real challenges of increasing populations, massive urbanisation and the impending ravages of climate change and biodiversity loss requiring radical rethinking of how to plan, design and manage our urban and rural landscapes, public realm and wilderness.

Landscape Architecture has a hugely significant role to play in this rebalancing of humans and nature, not only to restore natural systems and ecological integrity but also to deliver beautiful, engaging and memorable landscape and garden experiences. For these reasons the future for this profession has never been more important and the teaching of Landscape Architecture has never been more relevant.

Sheffield University has established itself as one of the international champions of landscape architecture and, through teaching, research and real life projects, is shaping a perspective of the future that will lead to an entirely new chapter in our landscape history. One that is rooted in science and rigorous understanding of natural processes but also open to our imagination and our capacity to create extraordinary new places and spaces. For these reasons I am very honoured to hold the title of Visiting Professor to the Department of Landscape at Sheffield University.

Even as a student myself in the early 1980’s I was very aware of the increasing focus on more ecological thinking in the way we should plan our world. I went on to set up Grant Associates to create landscapes with distinct identity and purpose but also with environmental integrity. Our particular emphasis has always been the connection of people to nature and the exploration of delight and ecology whilst addressing the C21st challenges of sustainability.

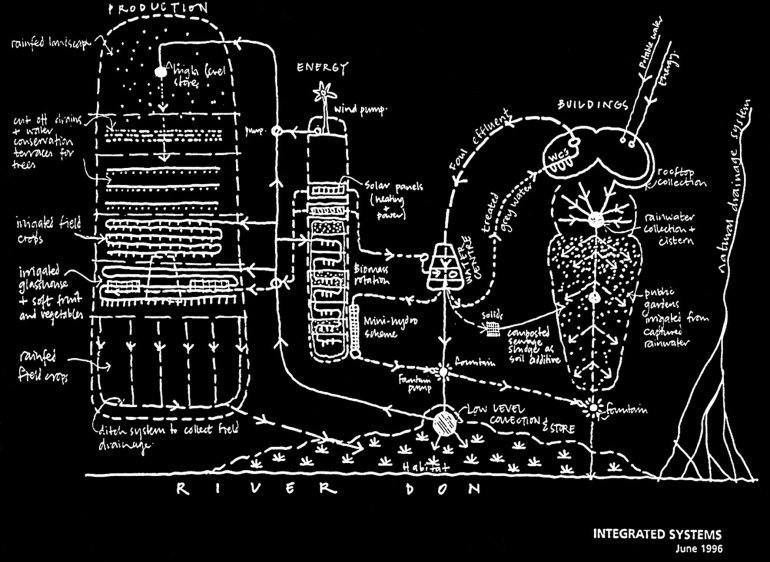

20 years ago the practice of sustainable development was in its infancy and I saw the opportunity to develop a landscape practice that had a strong focus on the creative interpretation of sustainable landscapes. Projects like the Earth Centre cemented this reputation and an approach to sustainable design and construction that has formed the basis of our work since (Incidentally, the first time I met and worked with James Hitchmough and Nigel Dunnett was on the Earth Centre project back in 1999). However, things change and today our understanding of the world, and how we can best influence the future, is quite different from when we started. New concepts of Natural Capital, Rewilding, Biophilia, Suds, Green and Blue Infrastructure and Ecosystem Services have permeated the language of landscape in an attempt to articulate parts of our future relationship with nature. However, these abstract ideas need to be interpreted within the design process and made real through the process of design and construction and so we recently decided to revisit and update our practice principles and values so we can go into the next 20 years with a renewed sense of adventure and a ground-breaking attitude.

Principle 1: One strong central idea

We believe our most distinctive and memorable projects grow from a strong central idea, typically influenced by some natural form or phenomenon. This in turn generates a whole ecosystem of thinking, geometry, form and character, often reinforced by a particular project approach to graphics and communication of the idea. As we have engaged with more complex urban and architecturally driven projects it has not always been appropriate or possible to apply these more naturalistic principles and we have applied our thinking in a more orthogonal and, perhaps, rational way. However, connecting our work to the wonder of nature is at the heart of our approach, and we know we can apply this to both urban and wilder environments.

Principle 2: Compelling communication

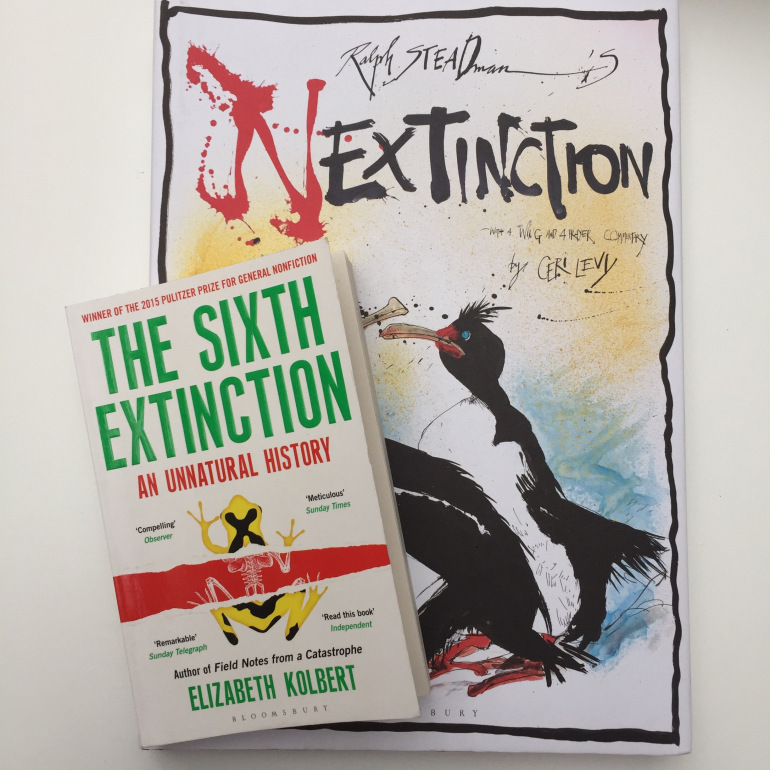

Looking forward, I want to set some new challenges to ourselves that are attuned to contemporary thinking on the relationship between Humans and Nature. Recently I have enjoyed a number of books that have rekindled my passion for learning and thinking. Not only scientific and moral reflections on the big global issues such as climate change but also books that inspire new ways of communicating ideas with clarity, humour and power. For me this is another fundamental part of the way we work - scientific and technical knowledge aligned with imagination, creative interpretation and compelling communication.

Two books illustrate this combination. Firstly the ‘Sixth Extinction’ by Elizabeth Kolbert articulates, with impeccable scientific rigour and beautiful writing, the inexorable, inevitable extinction of countless species across the globe caused by human actions. Secondly, ‘Nextinction’ is a graphic exposition of the extinction of bird species in which Ralph Steadman captures the madness, sadness and bewilderment of this extinction through the exuberance and anger of his illustrations. Together these two books are a great example of what we should be about in our work – passionate and articulate ideas communicated with energy and clarity.

Principle 3: Emphasize human emotions

Ultimately, most of our commissioned work is about the creation of places for people. 20 years ago we often used the language of sustainability to help us define the character and qualities of parks, streets, courtyards, gardens etc. Today I think we need to temper this reliance on the science and processes of landscape with a greater emphasis on emotional response, beauty, delight and wonder. Yes we need to deliver the spectrum of Suds, shelter, habitat creation, energy efficiency, well-being, food production, biodiversity, play, education and pragmatic functionality but we know people will only remember and value our landscapes if they feel a response to the experience. Through our projects we know this experience will always be greater if we can deliver some connection to our primal sense of nature or sense of wildness.

Andrew Grant, Visiting Professor Department of

Andrew Grant, Visiting Professor Department of

Landscape, Sheffield University